[This is one of six pieces in Jadaliyya`s electronic roundtable on the anniversary of the Algerian Revolution. Moderated by Muriam Haleh Davis, it features contributions from Ed McAllister, James McDougall, Malika Rahal, Natalya Vince, Samuel Everett, and Thomas Serres.]

Algiers, summer of 1972. A decade after independence and the newspapers are teeming. Algeria has recently been the first country in the region to successfully nationalize its oil and gas reserves; citizens enjoy free universal education for the first time; production begins at the gigantic new steel complex at El Hadjar; work is completed on the first of the 1000 villages socialistes near Tlemcen, agricultural laborers gain ownership of land under the Révolution Agraire; construction work is underway on the luxurious Hotel Aurassi, as well as Oscar Niemeyer’s Olympic Stadium and the Bab Ezzouar university campus in Algiers; worker self-management programs begin in state-owned companies; the first families move into the thousands of apartments that make up the new social housing complex in Badjarah; thousands of ideologically-motivated youngsters from around the world arrive to participate in Algeria’s future. In the capital, the bilingual residents of the cosmopolitan metropolis steer the latest Peugeot 504s down spotlessly clean streets lined with elegant bright white buildings toward the public beach resorts at Club des Pins and Moretti; women wearing white loosely draped ḥayeks or mini-skirts plan weekends in Paris with no need for visas; long-haired young men in flares drink beer or Pastis at pavement cafés; in the evening, people queue outside the Koutobia nightclub, from which echo the beats of the latest funk and soul hits.

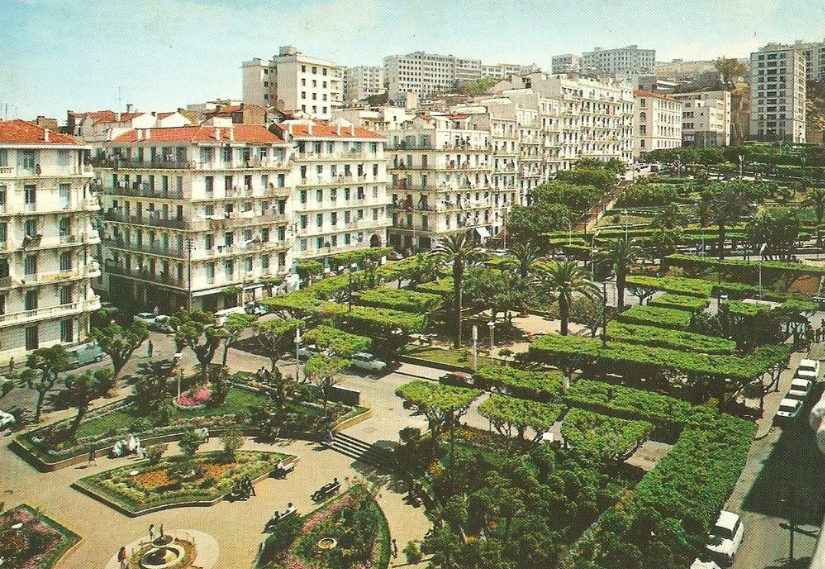

[Boulevard Abderrahmane Taleb, Bab el Oued, early 1970s. Image from Société Nationale d`Edition et de Diffusion (SNED).]

Fifty years after independence, these events and scenes seem not only to belong to another time, but to another world. How do people today remember the post-independence period and what do these memories tell us about the present? Wishing to move beyond the colonial period and the War of Independence, this article is based on ethnographic fieldwork over a one-year period in the working-class Algiers neighborhood of Bab el Oued. It looks at the ways in which contemporary subjectivities are articulated through references to the nation-building period of the 1970s under President Houari Boumediene.

What comes across most strongly in these representations of the period is the sense of past-present disjuncture, or of a temporal dislocation. There is a palpable sense that the present is not as it should be and that something important has retreated into the past. However, the relationship with the past in general – and with the 1970s more specifically – is ambivalent. This ambivalence is illustrated by the phrase yā ḥasra, which stands for both nostalgia and its opposite at the same time, variously denoting a wistful expression that things were better in the past, or an expression of relief that something negative in the past has had its day. Despite widespread nostalgia for the seventies, most of the people I met in Bab el Oued are happy to be rid of Boumediene’s authoritarian brand of socialist-inspired nation-building. The figure of Boumediene is divisive – he is simultaneously hated as a harsh dictator and respected for his integrity and sincere efforts to improve the lot of the average Algerian. Often both of these views belong to the same person. Boumediene was cast alternately in a positive light, as a strong leader delivering a combination of social justice and relative prosperity, stability and discipline), and spoken about negatively (as a merciless dictator that had political opponents eliminated, falsified the history of the liberation struggle, mismanaged state resources and repressed civil liberties). The legacy of authoritarianism was plain to see – most of the older people I interviewed told me before recording began that they felt uncomfortable talking about politics.

For middle-class residents tasting the benefits of material wealth in an economy that is certainly working for some, the Socialist planned economy is deemed responsible for creating a work-shy population that depended on the state and still expects everything to be handed to it on a plate. This is very much the capitalist narrative of entrepreneurial spirit. On the other hand, for working-class residents of the neighborhood struggling to make ends meet, the Boumediene era is remembered as being a time of full-employment and rising standards of living. One narrative claimed that despite the one-party state and lack of institutions that existed for much of the 1970s, Boumedienism’s focus on social justice – ensuring price controls, universal healthcare and social housing – made it more truly democratic than the current multi-party system, despite much greater freedom of expression in the present. For many people I talked to, the trappings of democracy mean little without social justice. One friend drew a clear distinction, couching today’s political system as a periodic redistribution of power among the elite in which the people have no say [therefore authoritarian] and 1970s authoritarianism as providing for people’s basic social needs [therefore more “truly democratic”]: “Before we had social justice but no democracy, now we have neither!” he said. This reversal goes to the heart of a debate about what democracy means to Algerians and reproduces the socialist-humanist propaganda of the 1970s, according to which democracy should be measured in schools, hospitals and land ownership – i.e. in social well-being, rather than in the number of parties in parliament.

Generational divisions also play a strong role in representations of the past. For older people who lived through the 1970s there is a strong sense of both the loss of the country’s early vitality and their own youth. The past is irretrievable and totally irreconcilable with a present in which they seem to struggle to locate themselves. On the other hand, many young people sit somewhere between traditional respect for elders, resentment that their parents’ generation grew up during what is perceived as Algeria’s heyday, and anger at the older generation who are held responsible for the country’s decline since the 1980s. As one graffiti in Bab el Oued defiantly declares, “Pourquoi nous? Cent pour cent skāra felli fessdou lebled” (Why us? 100 percent contempt for those who wrecked the country).

If the politics of the past is divisive, much less ambivalence is displayed when remembering the urban space and sociability of Bab el Oued in the 1970s. This is where representations seem unanimously nostalgic and where the feeling of past-present disjuncture is clearest. There is an overwhelming emphasis on aspects of the past that highlight that which is perceived as being lacking in the present, which is invariably cast in a negative light. Past-present disjuncture is read through the social, political, and economic changes that have occurred during the intervening periods – the economic liberalization and crisis of the 1980s, the violence of the 1990s, and the reinforced state power and consumerism of the 2000s.

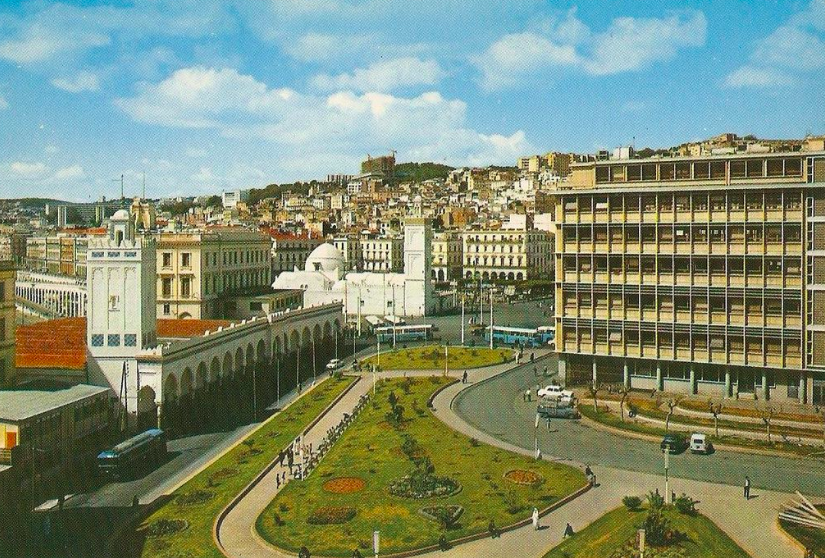

[The Great Mosque and park – now replaced by a multi-storey car park – early 1970s. Image from Société Nationale d`Edition et de Diffusion (SNED).

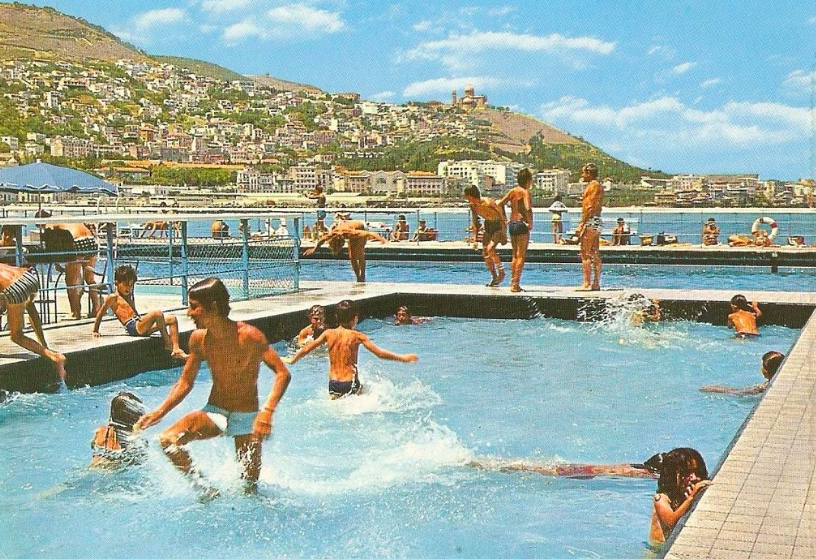

Descriptions of the 1970s depict spaciousness, a lack of traffic jams and crowds; there is clean, well-maintained urban infrastructure, and a sense that society was up-to-date with the latest fashions, cinema and music. I was told many times about the trucks that would nightly wash the streets with seawater, the uniforms worn by the city’s taxi drivers and the fines imposed on those spoiling the aesthetics of apartment buildings by hanging washing to dry on balconies. These images contrast with today’s overcrowded, congested, and dilapidated neighborhood whose cinemas and bars have closed and which offers virtually no spaces in which young people can express themselves. Nearby public resorts such as Club des Pins have long since become gated communities accessible only to the elite. Discussion of the past often includes condemnation of Bab el Oued’s degraded infrastructure in the present, especially the state of pavements and roads, the amount of uncollected rubbish in the streets and the dilapidated state of most apartment buildings. The seventies stands for seriousness in the management of public affairs – from urban infrastructure to lack of corruption – by a state that had not yet retreated from its responsibilities. The sense of temporal dislocation also goes hand in hand with an apparent spatial dislocation: while many older residents frequently complained about no longer recognizing their own neighborhood, many younger people struggled to recognize images of Bab el Oued’s streets taken during the seventies.

The sociability of the 1970s is seen as standing for a set of values that are currently in decline. The social relations of the time are viewed as being characterized by respect for tradition and the authority of elders, couched in terms of terbiya (politeness and good manners) and ḥorma (respect for social boundaries, particularly between men and women). The sociability of the seventies is depicted as being cohesive, with warm and cordial relations between neighbors. People knew each other and could trust one another. This is contrasted with the situation today, where mistrust of other people is often seen as being the norm and where state management of urban infrastructure seems to have been abandoned. This state of affairs is frequently couched as “ṭāg ‘la man ṭāg” (everyman for himself).

Memories of the 1970s are refracted through depictions of the appearance of serious economic crisis during the mid-1980s and the resulting increase in social disparities and decline in living conditions, and particularly through the social fragmentation brought by the violence of the 1990s. During the conflict, Bab el Oued experienced large-scale immigration from surrounding rural areas as people fled to the relative safety of the capital. Many of Bab el Oued’s residents saw their chance to escape and sold their apartments to newcomers, which means that people are now less likely to know their neighbors. In addition, the appearance of armed groups, bomb attacks, assassinations and the grim reality of having to get to work or school not knowing if one was to return alive, meant that people spent more time indoors.

While much media and academic attention has been given to the issue of who was doing the killing in Algeria, for residents of Bab el Oued the social production of mistrust between citizens compounded the total breakdown of state-society relations was compounded at the local level. People doubted not only who was who, but also who was informing on whom. Apartments were secured by steel doors and metal bars, and the days when children would move freely between apartments to visit their friends, and neighbors would stop to chat in the street, seemed well and truly over. Furthermore, the emergence of a consumer society and the measurement of success in terms of new cars and flat screen TVs in the more stable environment of the 2000s have further reduced social cohesion, as people increasingly act as individual consumers. Indeed a common criticism of the 1970s relates to the persistent shortages of consumer goods, as the planned economy found itself unable to keep up with increased demand fuelled by exponential population growth. Young people today simply cannot imagine going to the market and only being able to find green peppers and watermelons, or only being able to buy clothes made by SONITEX, the national textile company, especially since massive hypermarkets and malls have recently begun to appear on the outskirts of the city. Many older people seek to dignify what must have been far from ideal circumstances, with a fond smile and a sense of “we did not have much, but we were happy.”

In contrast to their parent’s recollections of a dignified past, to the young people that form the majority of Bab el Oued’s population the present seems to be anything but dignified. It offers only the meager prospect of endless daily struggles and humiliations - the struggle to combat boredom and stay out of trouble; to deal with an overcrowded city in which tempers can fray easily; to create a future for oneself despite nightmarish bureaucracy and an education system that does its best under difficult circumstances; to find some private space in which to stay positive and make the best of things.

[The swimming pools at Kettani, Bab el Oued, early-1970s. Image from Image from Société Nationale d`Edition et de Diffusion (SNED).]

In this sense, nostalgic remembering is a way of commiserating over the trials of life, cultivating intimacy through shared expression that allows people to define themselves in the world. Rather than a wish to turn back the clock, it allows people to express discontent with the way things have turned out, and to suggest that life should – and could – be better. Memories of the seventies depict the period as a time before globalization when Algerians were still firmly rooted in their own traditions, but were also embracing an exciting new modernism with confidence. In the social imagination of Bab el Oued, the decade represents a balance between tradition and modernity, precisely the areas in which the ideologies par excellence of the 1980s and 1990s – neo-liberalism and Islamism – accused it of failing. More importantly, these memories provide a sharp reminder that the challenges of Algerian independence – to build a democratic, social state that is at once modern and respectful of tradition – are still very much there for the taking.

[Click here to read the introduction or read other contributions].